Group gardening. Code Reviews Part 2: incentives, automation, and tooling.

A systematic approach

Part 1 was largely a discussion around why systemic approaches are needed in code reviews and the common issues that are faced in organizations as they grow and expand their scope. This section gets into how one can begin to improve their processes gradually towards an ideal state of fair and effective code reviews that don't feel like a slug fest for engineers, and better enable them to build amazing things. I must emphasize the gradual part of that last sentence. I do not advocate for throwing all of these techniques at a team all at once in hopes of improving things overnight and achieving some grand vision of perfection. Much like how Karl Popper advocates for a gradualist approach to social institutions seeking to improve the wellbeing of its citizens, large software engineering teams (and corporations generally) act as a mini form of a nation, and each of the below techniques may have interesting unintended side effects. As such it's best to chose the pieces that resonate best with your teams struggles, implement those, evaluate the effects, then apply more as needed.

An overarching theme you will see in all of these things though will be to systemize and automate them via clear software systems as much as possible, and in doing so minimize the need for any engineer to ask things like "How do I indicate this is a work in progress?" or "who do I need to ask to review this again?". We want to aim for clear discoverable systems and mechanics of code change over tribal knowledge transmitted via early morning standups when all involved lack the needed caffeine to remember any of it.

Draft PRs

A significant struggle of code reviews can be the intent of the code review in general, as a PR that is a work in progress might be reviewed very differently than one that is considered "final". One way to signal this in Github, BitBucket, GitLab, etc is via a feature called a "Draft PR". Gitlab and Bitbucket (finally as of this year) also support Draft PRs. This changes the UI in a clear way to indicate a PR is not fully ready to merge, and can even be hooked into automation systems to have different builds / checks / pipelines for Drafts vs non Drafts. Especially in distributed teams where the reviewers and the contributors may not even be awake and working during the same hours, this kind of obvious signalling is really important to reduce confusion and unneeded back and forth communications.

One way to signal PR intent I would avoid, are things like putting "DRAFT PR DO NOT MERGE" into the title of the PR as these things are easy to forget to do, easy to forget to update, and are often transmitted via spoken tribal knowledge that is hard for new people to pick up on, and hard to change in a consistent manner across the org once they become habit. Automated processes requires no habit. However, in a desperate pinch they can certainly work well to visually differentiate a PR against a list of other PR's in a repo. I've done it before. It just doesn't scale.

One unfortunate wrinkle in this though is that (as of this writing) for private repos in Github you need to be using a paid account to have access to Draft PRs. The next section can help with this if issue if you don't have access to an official Draft PR feature.

Description templates

Another great way to automate code review content and intent is via Description Templates. Github supports a checked in way of managing description templates so that every time someone opens a PR to that repo the description section is automatically filled with the contents of the template, as do the other major source control platform companies.

This feature can actually act as an excellent way to signal a Draft PR if the formal mechanism is behind a paywall for you. The top section of the template can be a section called something like "PR State" and contain checkboxes for "Ready for final review", "collaborative", "draft", etc. Each engineer then gets this description and fills it out on opening a PR, and can update it at any time. This has the advantage of being platform agnostic, though it may be harder to hook automation into. Having a template at all though is worth the time for a given repo, as will be discussed later.

Other ideas for templates would be a section for "Testing Instructions". I've seen this particular section be useful as it allows those outside the immediate development team to jump in and review the functionality of the code by not having to explicitly ask "what is this supposed to do?" It also acts as a form of systemized Rubber Duck Debugging for the person opening the PR as it requires one final time of the engineer thinking through what the code is supposed to do and going over the requirements for the task at hand. If you see frequent issues of small requirements being missed in PRs that were clearly described in the ticket, not isolated to a specific person, adding this extra step might be a good subtle addition to your PR workflow.

Having these kinds of automated requirements for each PR, regardless of the seniority of the person opening it, also helps to create a more flat and open culture on the team and discourage shortcuts or calls to seniority to push through code changes that no one understands the "why" of. The trick is balancing the level of process with efficiency of making changes. Push too far on PR process (this is the definition of bureaucracy you're creating here) and people won't want to even open PR's because it becomes burdensome. I'd say keep the number of templated sections to no more than 3, and the number of checkboxes to no more than a dozen. If you find yourself having more than that, there is probably an opportunity to automate those checks in the software itself instead of in the PR code review process.

Also consider mandating strict requirements on ticket contents for the task instead (I'm assuming each engineer task has a ticket), so that the ticket acts as the source of truth and information on expectations of the code, instead of the PR. That would also have the added benefit of clarifying work before engineers even begin writing code. Jira has many such tools around automating ticket contents and requirements. Use caution with heavy handed Jira features though as not all are actually beneficial, as well documented by No Boilerplate.

Comment Templates

Unintentionally toxic comments as mentioned in Part 1 can be a big issue, as can engineers whose stream of consciousness style of writing results in a novel length comment with no clear question or criticism that winds up spawning a meeting that isn't needed. If you are facing these issues one way forward is through the concept of a Conventional Comment. The strictness by which you implement these kinds of review comments is up to you, and in some cases even seeing that such a concept exists improves reviews instantly as people learn how to organize their thoughts. This is not meant as a shot at engineers in general, it is the opinion of the author that writing skills are poorly taught in American higher education for technical degrees, so many start their careers on a bad footing in this regard.

The benefits here of adopting Conventional Comments become especially strong when language barrier might be involved. On a personal note, I am terrible at asking questions in French and would love such a system if I was working with French teammates to help make my comments more clear. The more you can minimize confusion across time zones and cultures, the better.

One feature of conventional comments I would like to emphasize is the "Praise" comment, and how beneficial it can be to the culture of an organization. Some engineers severely dislike "noise" in their PR's and consider comments that point out something cool to be a waste of a notification and mental space. I have no data to back this up, but suspect most engineers do not fall in this category. They usually greatly appreciate such comments as long as there are not dozens and dozens of them to sort through. Use them sparingly, but know that compliments on ones work are greatly appreciated in a profession that begins to feel like the only time people say something to you is when something has gone wrong.

Conventional commits

git commit -m "."

Dude you changed 739 lines of code across 8 files...

Related is the concept of a "conventional commit", which is the act of applying an automated standard to git commit messages, though often for slightly different reasons. Conventional commits lay down rules around the info put inside of a git commit message.

git commit -m "<message_here>"

There is a range to how extreme you want to get here. One team at Yes Energy uses the git hooks feature to run a regex check against commit messages strings to make sure they start with the two letter, dash, number string combo of a Jira ticket, then checks that they contain some text after that. This check runs on the engineers machine and if a message fails the check, the git push fails forcing the engineer to amend the commit message. This ensures each commit is linked to a ticket for easier traversing of git history.

You can make use of git hooks to check all kinds of things and enforce custom rules. If you can regex it, you can hook it. Hooks can run at commit time, at push time, and a variety of other parts of the git workflow cycle. Check the docs for full details. A caveat is that each engineer needs to run a shell command to setup the hooks before they begin work on their machines, as hooks do not automatically configure themselves just by existing. If you are using devcontainers this setup can be fully automated on container creation via auto running a shell command in the Dockerfile, and there are probably ways to automate the hook setup on normal machines post clone.

Getting more extreme is the full concept of a Conventional Commit. One of the main goals of conventional commits is to take the "wait, what did we do this release?" memory jog out of the minds of the people writing release notes and into the hands of the engineers pushing code. Conventional Commits enforce structure to the commit message such that it can be parsed by automation later to look for bugfixes, breaking changes, feature additions, and many other things so that when it comes time to bump the semantic version number of your software and ship its change log it's all done automatically based off the commit messages. This level of strictness may not benefit most software orgs, but for those in heavily regulated spaces and those with very strict requirements visibility it can be a huge time saver in reviews and shipping code.

It will however change how engineers use git (that is the goal). With conventional commits doing things like "hey can you push that change to a branch so I can look at it?", or pushing commits at the end of the day to save work on a server (even if that code is in a broken state) becomes a little big trickier. Commits begin to act more like final save points with Conventional Commits, so many engineers in my experience under this system use two branches to do development. One as their "draft work in progress" that they never PR, and then a "final draft branch" they copy over all changes to once they're done, with a full conventional commit summary to save the work and put up a pull request on against that branch. This is extra overhead. Whether it is worth it is up to you and your team. When I worked on regulated medical device software it was a massive long term time saver.

The "resolved" button

How do you know when a specific piece of feedback has been adequately addressed? Does new code being pushed imply the issue is fixed? A similar social contract is needed between engineers to clearly indicate when all is good and both engineers can move on. The clearest way is to make use of the "Resolved" button in GitHub and similar software. Doing so minimizes the discussion thread and acts as a clear indicator that the conversation is done. Make use of this and do not merge code until all comments are resolved. This goes for "praise" comments too which as mentioned previously should be encourage. Add such comments and then mark them resolved so that the contributor will see them but at a lower priority visually than the comments that require fixes or active discussion.

To simplify history or not?

This line changed 47 times in the last month...

Using git log and git blame can be difficult when you have a lot of commits. This discourages engineers from making use of it and similar tools to investigate how code has changed over time which can increase the time it takes to debug an issue. As mentioned previously, conventional commits of all kinds can improve clarity here but still result in a lot of commits and small changes to sort through.

A more extreme solution is to enforce "squash and merge" at merge time on a PR. What this does is take all the commits used to create a PR, and compresses / squashes them down into a single commit representing the whole PR. This results in far fewer commits, but with more changes in the repo over time. The effects of this become significant given enough years of development in a code base, and makes history traversal far easier. This rule can be either used optionally at merge time by the engineers via the drop down menu options in GitHub or similar software, or hard enforced for the whole repo.

Automating the boring stuff

Use 4 spaces here, not a tab.

Markdown docs need to start with a # header.

Put this bracket on the next line.

Use a tab here, not 4 spaces.

If you see review comments like this in code reviews, your organization is wasting time and generating irritation among engineers. An important overarching theme of all of this, is reducing low value noise and small mistakes that add up significantly over time. These issues can be automated away via tools like spell checkers, linters, static analysis, and auto formatters. Prioritize adding these to your code base(s) for the technologies you use as they come up in review.

Here's a few my personal favorites over the last few years:

- Ruff (python linter and analysis)

- ESLINT (javascript linter and formatter)

- Code Spell Checker (spell checker for VS Code that can be customized per workspace)

- Prettier (javascript/css/html formatter)

- Markdown Lint (VS Code linter for .md files)

The code repo powering this blog uses Markdownlint, Code Spell Checker, and ESLINT if you wish to see a real example of the configs for those tools. They live in .markdownlint.json, cspell.json, and eslint.config.mjs respectively.

Ruff is a tool that I think deserves specific mention for its extraordinary features. It has linting rules so thorough that they can detect passive and active voice differences in doc strings in Python code, and highlights it right in the engineers editor before they even commit the code. If you wish to have a consistently readable code base, having automated rule sets in a tool like Ruff can be very beneficial in the long run, especially if you are developing an open source SDK for other people. Do you really need your engineers wasting review time arguing over what "active voice" is in a doc string?

Automating authority

Hey did you get The Dudes approval to merge this?

No I didn't know I needed to...

Uh oh

Another symptom of a growing organization that is in need of a structured conduct around code review is the issue of "who actually has the authority to say this is good to merge?". This is solvable problem, though it does require some adjusting to do in a way that doesn't annoy or overload critical engineers. A few tools can be mixed and matched here as needed for your team.

Default Reviewers saves the need to manually search and select people out of a list of reviewers, thus preventing forgetting people on code reviews. This does however potentially create a lot of notification noise for the people on the default reviewer list. Consider setting up communication channels for those on the lists to opt out if they are no longer needed, or add new people as they come on board.

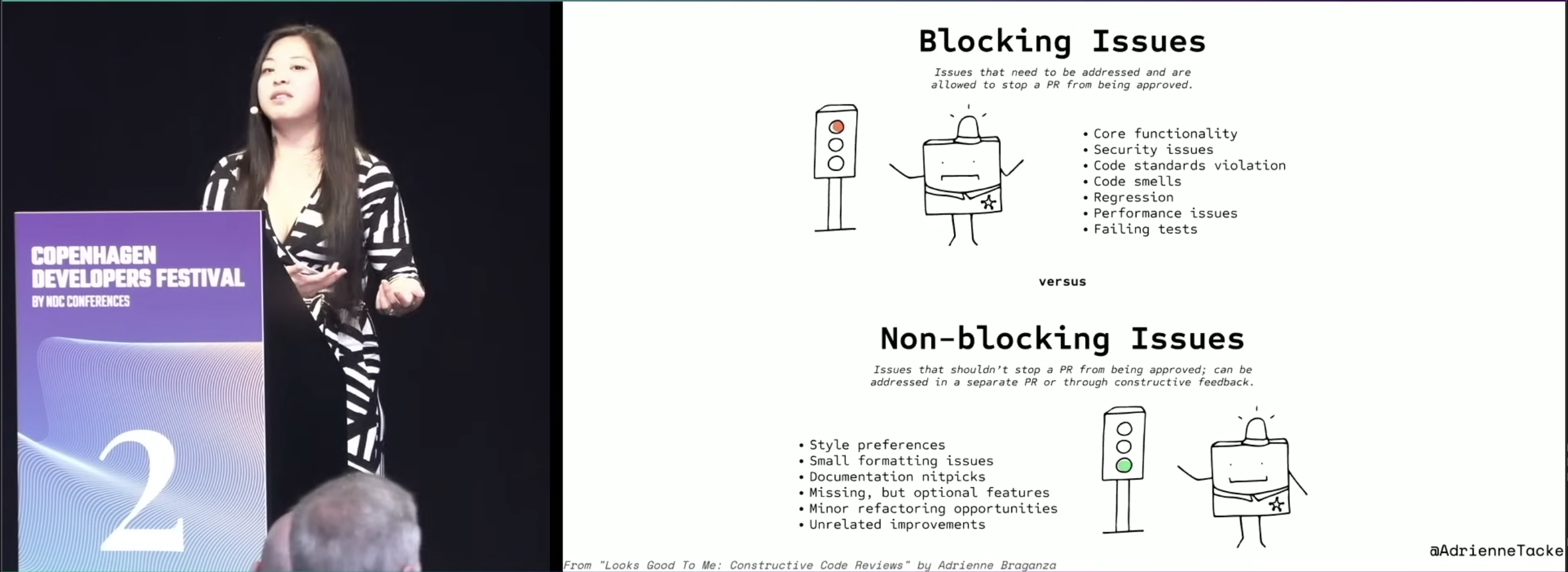

Besides answering the questions "who's approval is needed to unblock this PR?" you can also systemize "what issues are allowed to block a PR from merging?" This builds nicely off the concept of "conventional comments" as the two can inform each other like shown below from Adrienne Braganza presentation at Copenhagen Developers Festival.

There are a variety of tools that can accomplish this on all major source control platforms, from GitHub actions, to Jenkins pipelines.

Code Owners allows you to maintain a list of people who "own" a certain bit of the code, possibly those who wrote it. I find this feature should be used sparingly and saved for config files like Dockerfiles, compiler configs, Webpack configs, database configuration files, etc. These files aren't likely to change a lot, but when they do they have massive impacts on the system and downstream systems. Don't use this feature for common business logic methods that many engineers could understand and change. If you find that only one person understands your core business logic, that business logic needs work and you are in a dangerous position of siloed knowledge. Code Owners isn't the solution, cross training is. Speaking of which...

"Outside" reviews and durable knowledge

In the search for fast and thorough development it is easy to create brittle efficiency. If there is one engineer who is the best person to review code for a given code base, it's tempting to have them always be the person to review changes. That works great until that person goes on vacation, is way too busy with something else, or achieves the software engineer dream of retiring to be a goose farmer and never look at a screen ever again. The more you force a single highly skilled engineer to do nothing but review PR's all day, the faster they will achieve goose farmer.

Similar issues exist in organizations and systems world wide. The most efficient grocery store is the one who restocks the milk from the delivery truck at the exact moment a customer pulls the last one off the shelf and no sooner, with no extra space consumed by excess inventory sitting around. The most efficient power grid is the one that is on the edge of a blackout at all times with no generating facilities sitting idle. The most efficient hospital is the one with no empty beds, as empty beds represent a missed chance to do something else with the space. All of these systems work great when all is going according to the models, but one single event or combination of events that causes a significant deviation from the models (a diesel mechanic strike combined with a winter storm causing a truck to miss a delivery, a once in a century winter storm knocking out many generating assets, or a world pandemic respectively) causes the system to fall flat on its face in spectacular fashion.

This problem can also be countered with some smart automation. There is a concept referred to as an "informational reviewer" were people are pulled from a list of engineers who are not yet highly knowledgeable on the code at hand. This can be done via the Default Reviewer system with a maintained list of new engineers. It can be done at random via slackbot. It can be based off not being present in git blame outputs for the files changed in a code review and auto assigned via Jenkins pipeline integration. You get the point. The important part is that someone who has never seen that part of the code base suddenly gets pulled into the review and given the clear task of reviewing the changes. You can chose to give these people the power to approve and merge a PR, or you could not. It's up to you.

There are a few benefits to this and a cost. The cost should be rather obvious in that the review at hand will take longer with someone who is totally new to that code being involved and asking questions. Ignore the first order effect. This short term pain comes at the benefit of now systematically training engineers to be comfortable in code across the whole product or system, and doing so in a very organic way, every day, without you the manager doing a darn thing. Need someone to hunt a bug in some code but the main engineers for it are busy? You've already been training someone for months. Need a reviewer for the same reasons? You've got someone. It takes time to build up this knowledge around the organization but with a gradual expanding of the comfort zone of the whole team, you will get better long term results than throwing people into the fire without warning when The One Guy Who Knows This is unavailable.

This follows a principle well described in Atomic Habits by James Clear of being "1% better every day". It is very hard to understand complex code in one day when you get 1000 changed lines thrown at you, but build up gradual knowledge every week with constant interactions with the authors of that code? Thats a recipe for long term organizational prowess. It should be clear that this acts as a form of automated "knowledge silo breaking" which organizations often try to do with recorded presentations by senior engineers that no one watches or remembers. Ignore that failed technique, do it the organic and automated way using the tools you already have in source control systems.

Incentives and Goodharts Law

When putting up all this automation it is tempting to also add metrics to all of it for analysis by management when planning timelines or analyzing "productivity". Some of these kinds of metrics are rather useful and act as an effective tool to incentivize good engineering, some are less useful, and some are downright harmful even when well meaning.

Unit test metrics

One of my favorites was a simple one. At ArcherDX, where a Python code base was undergoing significant overhaul in preparation for conversion from Python 2.7 to 3.x, and also to be re-platformed onto a Docker container based system, the engineering managers decided that unit test coverage was something that needed to be increased significantly (starting near 0%) in order to make that future conversion safer. They implemented a simple bot in GitHub, such that whenever an engineer opened a PR the bot would post a comment on the PR showing the overall unit test coverage, and most importantly the change in coverage that the PR in question would induce. Green number when the percent was positive, red number when the percent was negative or 0. This incredibly small thing acted as a great automated reminder when someone forgot to write unit tests for new code, and acted as an incentive to increase coverage because who didn't like seeing the good green number go up? These sorts of bots are offered on many platforms and are also often trivial to write yourself if you already have a Jenkins (or similar) pipeline in place on PRs.

A word of caution. In theory more unit test coverage is good right? In practice it is, but only to a point. Focus on "branch coverage" as your metric as this does a better job of prioritizing interesting business logic (with logical branches) over boilerplate setup code than "line coverage" does. Even better is if you can find a way to prioritize files with known business logic first, because 20% coverage of core business logic code is far better than 20% coverage of one-line Java class setters and getters that do nothing interesting. This can usually be well achieved by having a board of tickets containing all files that need tests, and ordering them roughly by relative business logic importance. Maybe a bounty board of some kind?

The first question that always comes up when I bring up unit test coverage metrics is "what percent should we aim for?" A good question without a good answer. It will depend on the code base and how much interesting logic it contains relative to configuration and boilerplate code with no logic. I like to aim for 70% but that number is fuzzy at best and you know your code best. If your code base is succinct and business logic heavy and with little config class hierarchy code, go higher. If it's Java, your ambitions might be best being a little lower. The important thing is to set systems in place that move the trend line in the right direction. To be clear, it is not that I think unit testing config and setup code is worthless, it can catch situations of misconfiguration and unintended side effects when done well, but it should not be a high priority.

Chasing numbers

Another word of caution though with metrics. When deciding what numbers should be prioritized you must question the second order effects of doing so. Incentivize engineers to write more lines of code and you'll get fluffy, overly engineered code with pointless layers of classes, with a newline everywhere that one can be allowed by the compiler / interpreter. Incentivize QA to open a lot of bug tickets and you'll get QA opening spurious bug tickets or even breaking the software in unrealistic ways that no user could ever do (like messing with Kubernetes pods to break things on purpose as I saw QA do at one organization) in order to open as many tickets as possible, thus wasting engineering time and putting engineering and QA on a hostile footing towards one another. This all too human tendency to follow metrics to the point of absurdity causing those metrics to thus become worthless is known as Goodhart's Law. Chose your numbers wisely.

On a lighter note, comedy can be a powerful tool for keeping engineering lighthearted and yet on the right track. "Number of failed nightly builds" was one metric that, though not measured directly, was incentivized at one of my previous companies by using a bobble head trophy that sat on the desk of the engineer who broke the build. This worked great until one engineer liked said trophy so much he started breaking things on purpose, thus proving Goodhart right yet again.

ADRs and the systemizing of tribal knowledge

How do you prevent the situation of only a few individuals knowing why an application was built the way it was? Or why a network of applications communicate the way they do? How do you prevent the inevitable brain drain that occurs as natural attrition causes these people to move on? The previous systems are aimed to help with this issue, although somewhat indirectly. The direct approach is by instituting something called an Architectural Decision Record as part of the normal software development process. As mentioned in GitHub page on ADRs, they can be as formal or informal, as detailed or light as you want. The point is to create a record of information, stored right next to the code that documents the big "why" questions. These docs can then be searched through with a number of command line and UI tools to reduce confusion and give context to the system, and be used to inform future decisions. Your level of enforcing these docs to be created and updated it also up to you, from a check box in the PR description template, a hook check for .md updates, Jenkins pipelines that check for changes in known critical files that then checks for .md updates, etc. Or just good old cultural "we always write down these kinds of decisions for later" if your organization can make that work.

I mention "stored right next to the code". They should be not only stored in source control but stored in a format that source control works well for, meaning not a Word doc or PDF. Besides being dreadful when analyzed with typical text tools and git, these formats lock you to vendors and platforms that may not always be in your best interest. My favorite format is markdown, although other plain text formats can work well too. Markdown has a number of advantages though that are well documented in The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Plain Text by No Boilerplate.

Building your future chronicler

There is a final added benefit of all these systems. We have created, institutionally, automatically, a vast amount of data about human decisions making and the history of your project in reliable forms, preserved forever in git and its related tools. This data is intended for human consumption, and a skilled software engineer who knows their way around git log, git diff and grep can do amazing things with so much info at hand. But there is another reason to do all this that is very far looking. With all this data at hand, AI systems will be able to better answer "why" questions about your code and its history.

As of this writing, modern LLM's do a decent job of reading code and telling you what it does, although its utility diminishes with the complexity of the code and how niche the technologies are. However, given the advances seen in recent years in the machine learning space generally (and especially beyond LLMs) we can likely bet the improvement in coming years will also be remarkable. Somewhere between "Man what a time saver" and the writings of Ray Kurzweil. Once you feed enough review comments that are well structured, ADRs, "why" comments in code, and well written git commit message histories into such a system you now have the recipe for AI assistants to your engineers that can answer domain specific questions previously reserved to wrangling mythical long beard code slingers who no longer work at your company. The goose farmer can retire in peace.

It is the opinion of the author that the ability to write well and clearly about complex systems will not be reduced in importance due to AI, on the contrary it will be greatly increased. AI systems are built off of records and models of human reasoning, and to create new and better AI systems (especially those customized to a specific application) we will need new and better records of human thinking.