Group gardening. Code Reviews Part 1: communicating critique, documentation, and review culture.

Code reviews are hard, and doing them well requires a special blend of technological knowledge, reasoning skills, people skills, project historical knowledge, writing skills, and cultural / language understandings that often don't overlap in any one person. On top of this, what is best for one team and the technology they work on may not work well for another so it's hard to have one set of absolute rules for how all of the software industry does reviews. I however would argue that there are common guidelines that can help improve all code reviews that share roots in human institutions generally.

What follows below are my own musings on what works well on PR's and most importantly what doesn't work well. It is the combination of many years of first hand experience, combined with books, videos, and articles that have inspired me. I stand on the experiences of many giants that I will source throughout the two parts of this blog series. For some context, in my career I've worked on heavily regulated medical device software approved by the FDA, cloud data management software for huge companies, power grid data analysis software, and dozens of small group hobby projects, with teams from all around the world and dozens of languages. I'd hardly call myself an "expert" (that's a strong word) but I've seen a rather wide swath of the software world.

The advice and opinions within will oscillate between being from the perspective of the one looking at the proposed code changes (reviewer) and the one who wrote the changes themselves (contributor). I hope these ideas will help to improve the clarity of your code reviews along with their usefulness to others, historical value, efficiency of workflows, knowledge sharing, and general morale of your teams. Part 1 will focus on the "why" of general code review culture and processes while Part 2 will focus on the "how" of what to do about it with tooling and automation to support that culture with an eye toward the long term future of the code base and teams building it.

Reviewer comments, feedback, and separating code from the human being

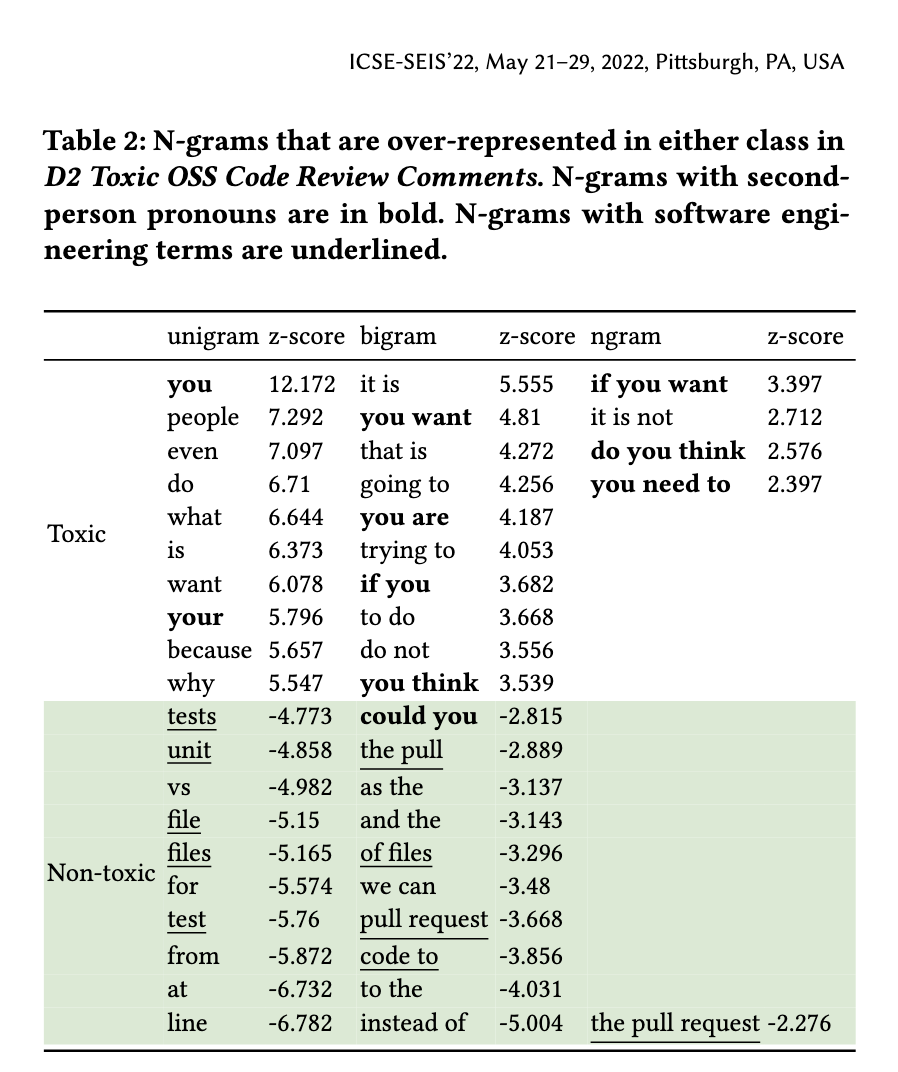

One of the difficulties with code reviews is the potential to create interpersonal tensions and conflicts among coworkers who have previously worked well together. There can be a huge difference in working side by side with a person pair programming, vs having a stream of cold toned notifications hit your inbox seemingly roasting everything about your recent proposed code changes. Particular among these are review comments that are either intentionally or unintentionally accusatory and focus on the person writing the code instead of the code itself. These tend to be "to the man" code comments that use second person pronouns as found in this study of toxic code comments. I've copied Table 2 from the study below to illustrate this.

Software dev is a form of group gardening, and the focus needs to be on the work at hand, not the one doing the work.

Similarly difficult comments are ones like "something isn't right here", "this could be better", "do X instead" but for completely different reasons. These review comments leave the contributor having to guess the mind of the reviewer, and usually result in follow up questions that could have been avoided. Comments need to be specific in their suggestion and justified in why, so that it can be a form of learning experience for all involved and not just the contributor but those reading it later on as a form of historical document.

Knowing all this is great but what does one do about it? When a team is small enough it can suffice to simply say these things in a meeting. Blessed are those who work on a team of 3 engineers and can form culture and process so efficiently. This however does not scale, with people or with time. Things said in a meeting are too easy to forget or misremember, and new team members often have the audacity to have not attended past meetings from before they were hired.

There are a few ways forward. One immediate method for smaller teams is to have a doc that defines how code review feedback should be structured to avoid vague, toxic, and unhelpful comments. Store this in markdown text format in the root of the code git repo. Each repo might have slightly different needs so having a dedicated one for each, even just copy pasted, might be helpful. Alternatively put it in git repo dedicated to this type of documentation. Google Drive, Confluence, and its ilk are where knowledge for engineers goes to die. The best place to store such knowledge is in a place and format engineers know how to search and traverse well. Raw text stored in source control. I have this video by No Boilerplate to thank for giving voice to years of my own frustrations with technical documentation systems.

Another way forward though that scales even better across the organization is to automate the structure of code comments. Here's a preview for Part 2.

Intent signalling

"Why are you showing me this if it's not ready to merge?" is a harrowing question to get from a coworker. It comes from a difference of assumed intent and assumed workflows. This particular issue can especially surface when an organization goes through mergers and acquisitions, or brings on a group of new engineers from the outside who come from a different background of how their code review process works. Most of these differences go unspoken and maybe not even consciously realized.

Some groups use PRs as a way to show early work and get initial feedback before they commit too much effort, with no intention to merge until more work is done. Some groups treat PR's as a true "final draft" that should represent "perfect" work that is ready to merge and the contributor has no interest in hearing feedback or alternative solutions to the problem at hand. Most groups land somewhere in between, where the contributor is open to alternative suggestions and the PR might go through a few cycles of "comments and revision suggestions" -> (new code pushed) -> "more comments and revisions" -> (more new code pushed) -> PR is finally merged. What's important is realizing these differences in workflow attitude exist across the industry and making an effort to clearly signal intent when opening the PR to avoid frustrations or confusions for all involved, as each workflow type can be beneficial when used well.

Merge blocking and authority signalling

Another subtle tension can occur when a contributor merges a PR that a reviewer has left comments on that the reviewer expected to have resolved before merging. There is an assumption that by leaving a comment, it will be addressed, while the contributor may have read that comment as more of a suggestion to consider than something that needed to be done and hus they charge forward. This issue becomes more significant in my experience with distributed teams who haven't worked together in person or have language barriers.

Similar to signaling PR intent, clearly signalling of revision / merge blocking intent is also critical to helping ease the review processes. Which reviewers must approve before merging if any? What kinds of reviewer criticisms must be addressed? How do you decide that they are addressed at all? These questions are easier to answer the smaller the team is and the closer they work together in person, but the larger spread the team is in manpower, time, and space the more of an issue these types of communications become and the more development slows and becomes painful. These miscommunications can be small and easily moved on from, or large and cause significant tensions and conflicts.

Seek ways to communicate through the common tools already being used by all engineers, and resist the urge to add yet another vendor subscription onto your pile of software. There is usually a more elegant way to solve these communication issues with the tools you already have. In Part 2 we'll look at effective tools for smoothing out these issues and speeding core reviews of distributed systems by create a type of automated social contract around authority on reviews.

In-code Comments

I'm bound to ruffle some feathers with this one but I don't like the majority of code comments. They tend to be redundant to the code itself and create more issues down the line as the underlying code changes and the comments themselves aren't changed. The only thing worse than confusing uncommented code is confusing code that has comments that lie. Such noise clutters diffs and takes up mental space. Here's a random example I found online for some trivial Go code:

func main() {

// define the variables we want to add

var number1, number2, number3 int

// initializing the variables

number1 = 99

number2 = 81

// adding the numbers

number3 = number1 + number2

// printing the results

fmt.Println("The addition of ", number1, " and ", number2, " is \n ", number3, "\n(Addition of two integers within the function)")

}

These comments are unhelpful to reviewers and future devs, and in this case were likely just AI generated. Your comments should describe why the code is written the way it is, along with documenting potential side effects that aren't obvious to most engineers. What qualifies as "most" is of course imprecise and dependent on the team and their tech. In the above example, a comment on why fmt.Println() is being used and not some other logging library would be much more interesting depending on the context of where this code appeared.

One interesting exception to this though can occur with sufficiently complex programming (despite best efforts to simplify) and a team that is relatively new to the technology, or involves a technology that few have ever seen and thus might trip people in the future. You'll know this situation when engineers are frequently having a hard time even understanding basic syntax and use cases for the code at hand and find themselves asking for help stepping through it. I ran into this situation recently on a project where Espertech was being used for some live power grid data processing. For everyone out there other than the 12 people who have used Espertech before, Esper is hard and almost no one coming onto the project will have ever seen it before. As a result we left a significant amount of pure descriptive comments (violating my above rules about not using such comments) in the code, and especially code comments on lines where a library method had unintuitive behavior. In general, third party libraries tend to be good situations to use purely descriptive comments, as reading the source code may prove difficult depending on the tech compared to your own source code.

To even realize that people are confused, you MUST have a team culture that allows people to feel safe asking questions and getting help without fear of "looking stupid" or incompetent. An aggressive culture of stack ranking, PR hazing, and ignoring people when they reach out for help because everyone is too busy will stifle the ability to clear up knowledge gaps and mostly filter for those who like to bluff their way through misunderstandings or ignorance. These effects are subtle and toxic in a real sense because their damage spreads like a toxin or a cancer.

Unit tests

Unit tests are the gold standard for the entry point of reviewing a code change. It presents a set of small expected behaviors that when combined with a debugger, allows those new to the code to step through its execution line by line, requirement by requirement, to understand and verify that a code change does what it is supposed to do. It is atomic, and self discoverable.

Contrary to feature code itself, comments that describe basic expected functionality of a unit test are very helpful in the form of a unit test function doc string, as it conveys the intent of the test which itself is likely a requirement of a large feature for the end product. It is a form of automated acceptance criteria documentation. I'm a big fan of the "Given that...verify that..." format of unit test doc strings, but many such useful standards exist. Unit test doc strings can still suffer from not being updated when testing logic changes, but in my experience that happens at far lower frequency than feature code comments being forgotten. Consider code reviews to be yet another reason to push for unit tests in a code base.

As a very direct example of the utility of unit tests in understanding code functionality for reviewers, I am now tasking you with reviewing an app built with Espertech. The Espertech GitHub repo features an examples directory that not only has real world example programs using Esper (far beyond worthless "foo-bar"), but also features a unit testing suite for each one. Take a moment as someone who has never seen this technology before to look at one of the example projects that uses Espertech, be confused by it, then look at the unit test code for it. The effect is remarkable.

Commit messages

I've written my fair share of holy crap it works commit messages. As a matter of fact I gave a presentation to Yes Energy's various engineering teams on PR best practices with another engineer where I showed a screenshot of one of my commits with that exact message as an example of what not to do. We all have our moments.

Commit messages represent an under utilized way to communicate history and intent of changes. Many software engineers don't know that git log and its related tools even exist, but the moment they are shown the power of traversing the history of a codebase, they begin to use commit messages differently. Suddenly its yet another data point to make sense of the past and hunt bugs, and burdensome when not used well.

There are many ways to use these commit messages, and how strict one should get about them (from laissez faire style messages to squash and merge / rebasing on merge and thus deleting them completely) is a discussion that should be had with the team and their preferences, then documented in an easy to reference form of some sort when the rules need to be consulted. Ideally, a markdown doc in the relevant repo. As with most things though in software, consistency is the key and many automation tools exist to ease the enforcement of rules and standards around comments. The greater the consistency, the more one can lean on grep and other search tools for understanding the history of a repo. These consistency tools include git hooks, conventional commits, forced squash and merge, and others that will be looked at it more detail in Part 2.

The Open Code Review Society and It's Enemies

What all these ideas build up to is a form of code review social engineering that attempts to counter balance the worst of human nature when critiques are flying, with a structured and systemized approach that builds on the best parts of human reasoning and teamwork while minimizing miscommunication, especially on distributed teams with cultural and language barriers. Much like how social institutions in government seek to incentivize the best in their people and counteract the worst through laws and codes of conduct, engineering teams in companies can fall into the same traps, and require the same systemic solutions. We are all human after all.

What one should try to achieve in a code review is something like the ideal of scientific peer review, where the ideas at hand are tested, criticized, and improved, regardless of the contributor and without personal attack. A fair, rule bound, structured playing field for code reviews allows for the rooting out of bad ideas that doesn't revolve around specific individuals while helping to prevent bias, seniority, and reputation from favoring certain individuals. It solves the same "succession problem" that government seeks to solve through elections and process, instead of family based autocracies. It is a commitment to gradual improvement and iteration rather than relying on the utopian vision of one individual and their opinions. By expecting or requiring a review structure where code critiques must be supported by clear reasoning, even clearer expectations, and rules of progression that all can understand and referenced, those experienced engineers will also more consistently pass on their knowledge and reasoning skills to others, improving mentoring and reducing the siloing of knowledge.

In Part 2 I'll dive into the mechanics of how one can create such a review system, and begin to fine tune it for your own teams.

Sources

The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Plaintext by No Boiler

Looks Good to Me by Adrienne Braganza

Looks Good to Me by Adrienne Braganza at Copenhagen Developers Festival